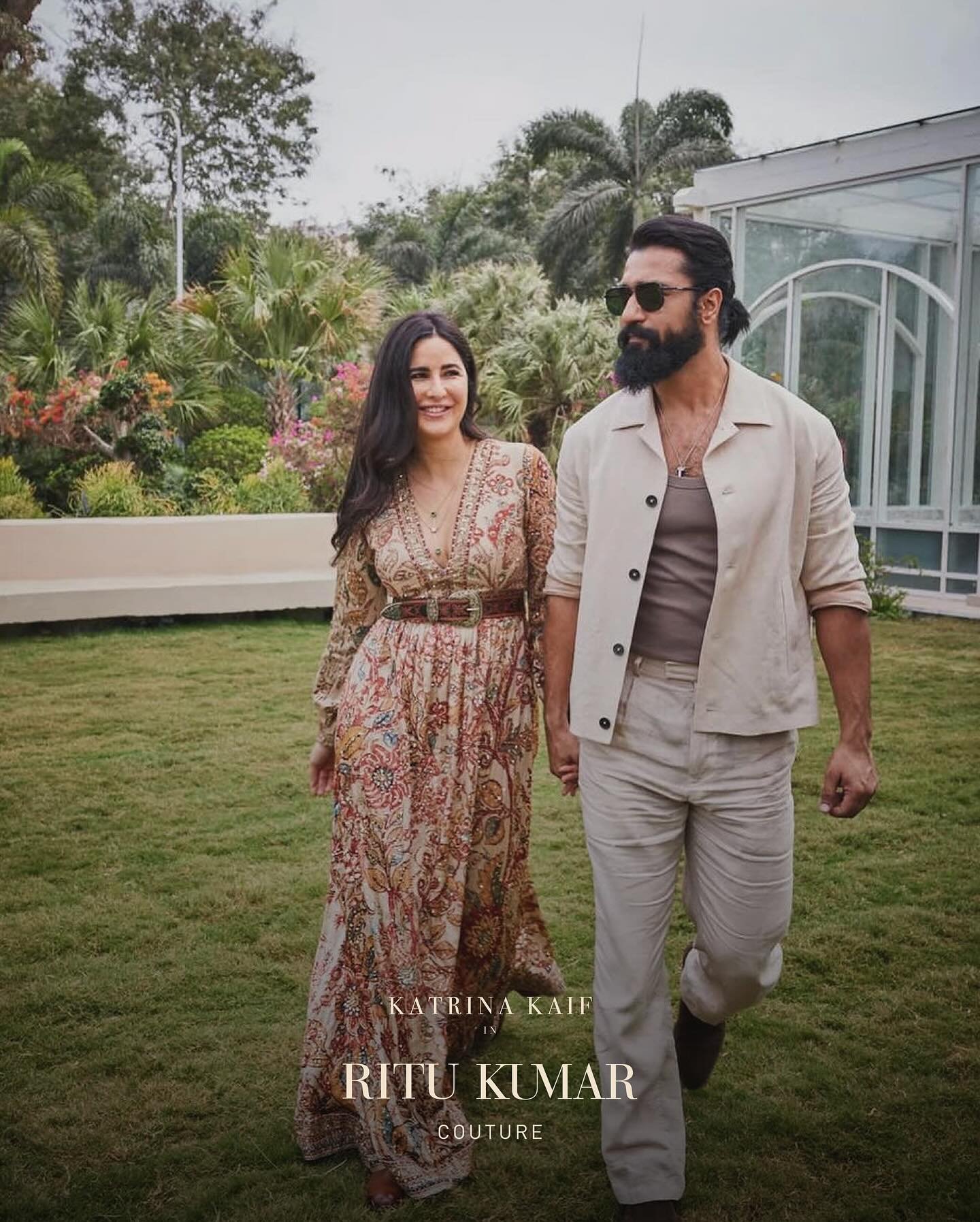

Considered the earliest jewel in the crown that is Indian fashion and design, Ritu Kumar, who turned 80 this November, vows to never retire, even as she chooses to focus on research.

By Nichola Marie

When veteran fashion designer Ritu Kumar was awarded the Padmashree in 2013, she was the first mainstream Indian designer who had been accorded this honour. “They’ve never had a category where designers were awarded,” she had pointed out in amazement at the time, adding, “the awards went to people from art, cinema, dance and music. I’m happy that design is now also being considered and it will give us so many more opportunities to work for our own craft.”

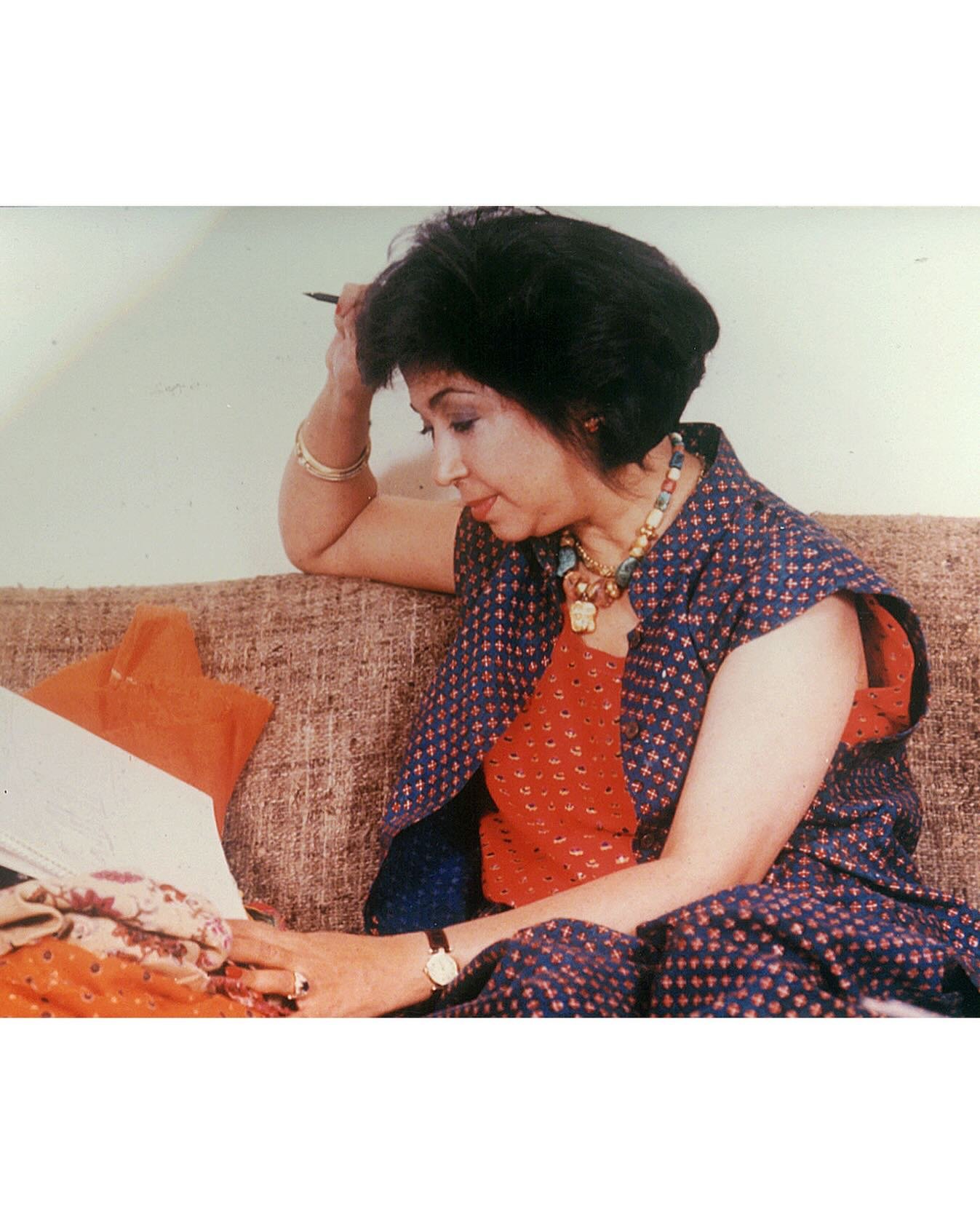

India’s pioneering fashion designer, who has been making clothes for approximately 55 years — longer than anyone else in the country — had started out even before the terms ‘fashion’, ‘designer’ or ‘retail’ existed in India’s clothing vocabulary. Transforming into one of India’s finest and foremost designers, she has long since acquired widespread acclaim for her unique style that weaves ancient Indian craftsmanship with contemporary aesthetics.

A Connectivity Of Chemistry

A pivotal figure in the revival of Indian textiles on global platforms, Kumar’s design philosophy is deeply rooted in the rich textile heritage of India, with a strong emphasis on sustainability and artisanal techniques. Her collections thus often honour the past while embracing the present. With an unmatched legacy in crafts revival, as well as in pioneering entrepreneurship, Kumar is considered to have practically given the prototype for the rest of the Indian fashion industry. At 80, she continues to redefine Indian fashion, her commitment to craftsmanship and sustainability enhancing her designs as she contributes to preserving India’s rich textile heritage for future generations.

Yet, Kumar refuses to take credit for starting anything, maintaining, “Indian textile crafts are so rich and I am a nobody. I could not design a block, or print with one, or create an alchemy of colours like the dyers did. I just join the dots.”

She believes that India has an organic and indigenous handwriting in fashion, and Indian designers are more catalysts. “Wars were fought with the French, the British, and the Dutch on trade routes to take textiles out of our country,” she says. “We have a very old connectivity of chemistry of understanding yarns, the alchemy of dyes — no other country has it. And the fact that we’re still doing that is phenomenal.”

Starting Point

Born in 1944 in Amritsar into the comfort of a home enlivened by a joint family, surrounded by affectionate aunts and uncles, she moved during her early years to Simla to study at the Loreto Convent Tara Hall. She went on to pursue Home Science and a Bachelor of Education at Lady Irwin College in Delhi. It was also here that she met her classmate’s brother Shashi Kumar, who lived in Calcutta (Kolkata) and was in the family business – the man she would later marry. She was attracted to his sophistication and then there was their mutual interest in books.

The foundations of Kumar’s journey as an entrepreneur were laid at home itself. Her educated and broad-minded family ensured she received a good education and also conditioned her to be independent. While she shared a great emotional bond with her mother, she would discuss careers with her father, who had academic ambitions for her.

Kumar graduated in 1964, following which she won a scholarship to study Theatre and History of Art at Briarcliff College in the USA. She returned to India two years later, acutely aware of the gap in her knowledge about Indian art and heritage. Shortly after she wed at 21 in erstwhile Calcutta, she took up museology studies at the Ashutosh Museum of Indian Art. Discovering various forms of dying embroideries and prints gave her valuable insight into a world she had never seen before. It was the start of a passion that would only grow greater with time.

Interestingly, her involvement with textiles itself began in an entirely serendipitous manner. As Kumar narrated in an interview with ‘Mid-Day’, “I stumbled upon a village called Serampore, a former Dutch colony on the outskirts of Calcutta, where their indigenous art of printing had been systematically wiped out by the British. There was so much talent there, hindered by the lack of employment opportunities — there wasn’t any retail space around, which was killing that rich heritage. I got interested, designed a few blocks and the workers printed a few saris using them. That’s how my first set of saris came out. Pure accident!”

It wasn’t long before the workers began producing saris for Kumar and she went on to hold her first exhibition at Calcutta’s Park Hotel, which — to her surprise — was a hit. It led to her opening a small retail space. On visits to museums around the world, she sourced printing blocks which she passed on to her workers. While the business did not exactly take off with a bang, growth was evident. She rues that the 150 years of British rule had created an art vacuum of sorts in the country, leaving a lack of books and museums. Her patience and determination kept her going and success eventually dawned.

Partnering her on this journey, were her husband whose business background rendered her venture commercially successful, and her children Ashvin and Amrish, who, from a young age, would accompany her on all site visits as she juggled to balance home and work.

Growth Curve

Kumar’s designs, based on her study of textiles and embroideries, caught the eye of the dealers in Chandni Chowk, who took the copies to the masses. Far from being outraged, she observes, “They are so important. I tell you, we on the ramps have no impact. When it really works is when it is copied.”

Kumar was also the first Indian, along with Fabindia, to enter the realm of ready-to-wear retail as early as the 1980s. She explains in an interview with ‘The Week’, “We are not a country with only one handwriting. The folk and the one-of-a-kind coexist. If we have a buti done for a Jaipur royal and a refined buti in Bagru, neither is a poor cousin of the other.”

The label went from strength to strength. In 2002, her son Amrish launched a mass line called Label in order to create more product categories, and in 2021, another one called Aarke. In 2019, the Ritu Kumar label diversified into home furnishings. The Ritu Kumar label still comprises the biggest chunk of the pie, with Label coming in second, Ri (bridal) and Aarke next, and Home still growing. The company also integrated into a strategic partnership with Reliance Brands in 2022, with the corporate house now owning 52% of the company, and being in charge of finance, administration and HR.

Today, the designer brand has over 50 stores across India, as well as an increasing international footprint. The brand’s commitment to high-quality craftsmanship and customer satisfaction is evident in its growing team of over 800 employees. It continues to strike a fine balance between its innate roots and becoming a multi-billion dollar business with an expansive family of craftspeople and collections that straddle many worlds. Its rising number of stores is testament to Ritu Kumar’s dedication to delivering a refined, customer-centric retail experience.

Looking Forward

Kumar’s journey spanning many decades has also been witness to several changes in the industry. It goes without saying that rather than seeing the younger designers in the space as competition, she believes budding designers should only be encouraged and mentored. Kumar also points out that nowhere in the world does any country have indigenous fashion handwriting anymore. “It’s totally dictated by Euro-centric fashion, owned and sold by multinationals and designed by a dozen fashion houses,” she observes, adding, “in such a scenario, we are probably the only country where people wear their own clothes. So, when it comes to competition, it isn’t between the designers of this country, but to maintain our identity amongst the various international brands.”

Despite her many achievements, she still yearns to help improve the handloom sector and reduce its inherent problems such as unemployment.

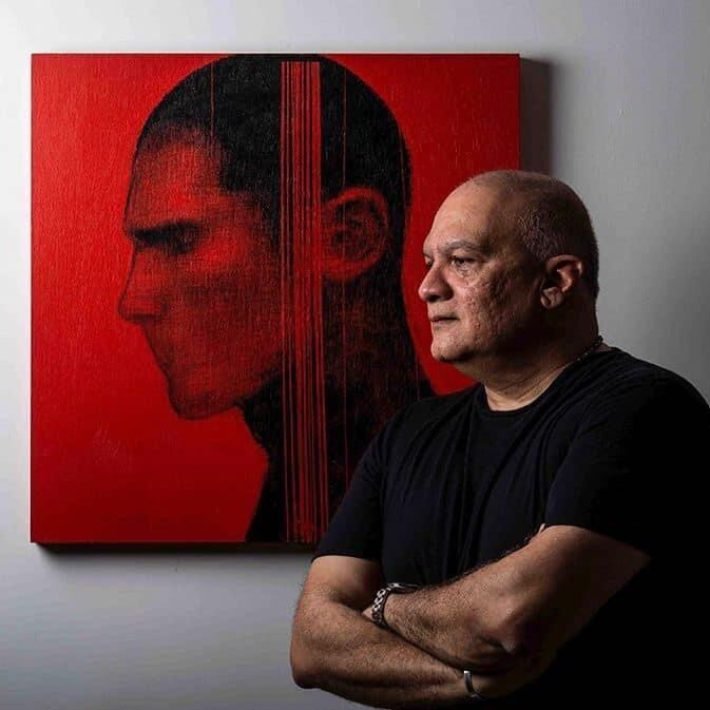

An avid collector of textile fabrics, blueprints, shawls, and actual embroideries from museums and dealers, she believes some of the things she has bought for herself should be put into a museum, alongside her entire repertoire of designs. “Education in our field is very important, but so patchy,” she points out.

She is also bringing out a book with curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul. With the working title ‘Yatra’, it will take the reader to all the areas Kumar has worked in. “It tells you where to go, where to stay, how to get there and who to meet. Younger people need to take over India’s textile traditions, and they need to rough it out, too,” she emphasises.

Kumar has retained her passion for studying history and textiles. She also continues to travel the country, discovering places and activities that have never been documented. Listening to Indian classical music and watching Bollywood and Hollywood films in her downtime, she has a soft spot for classics such as ‘Mughal-E-Azam’, ‘Pakeezah’, ‘Gone With The Wind’ and older Bond films. Spending time with family ranks high on her list of priorities, with regular family vacations that promote bonding.

She adds, “I will never retire, but I volunteered to focus on research. There are too many openings of retail spaces now, and I cannot keep up. We are the first company where the next generation is the creative head. I don’t want to be hands-on. I want to write and I want to paint.” Her occasional health issues including a spinal injury haven’t dampened her sense of humour, as she jokes, “I can’t walk the ramp now. I cannot even drink Scotch anymore… I can only drink wine now.”