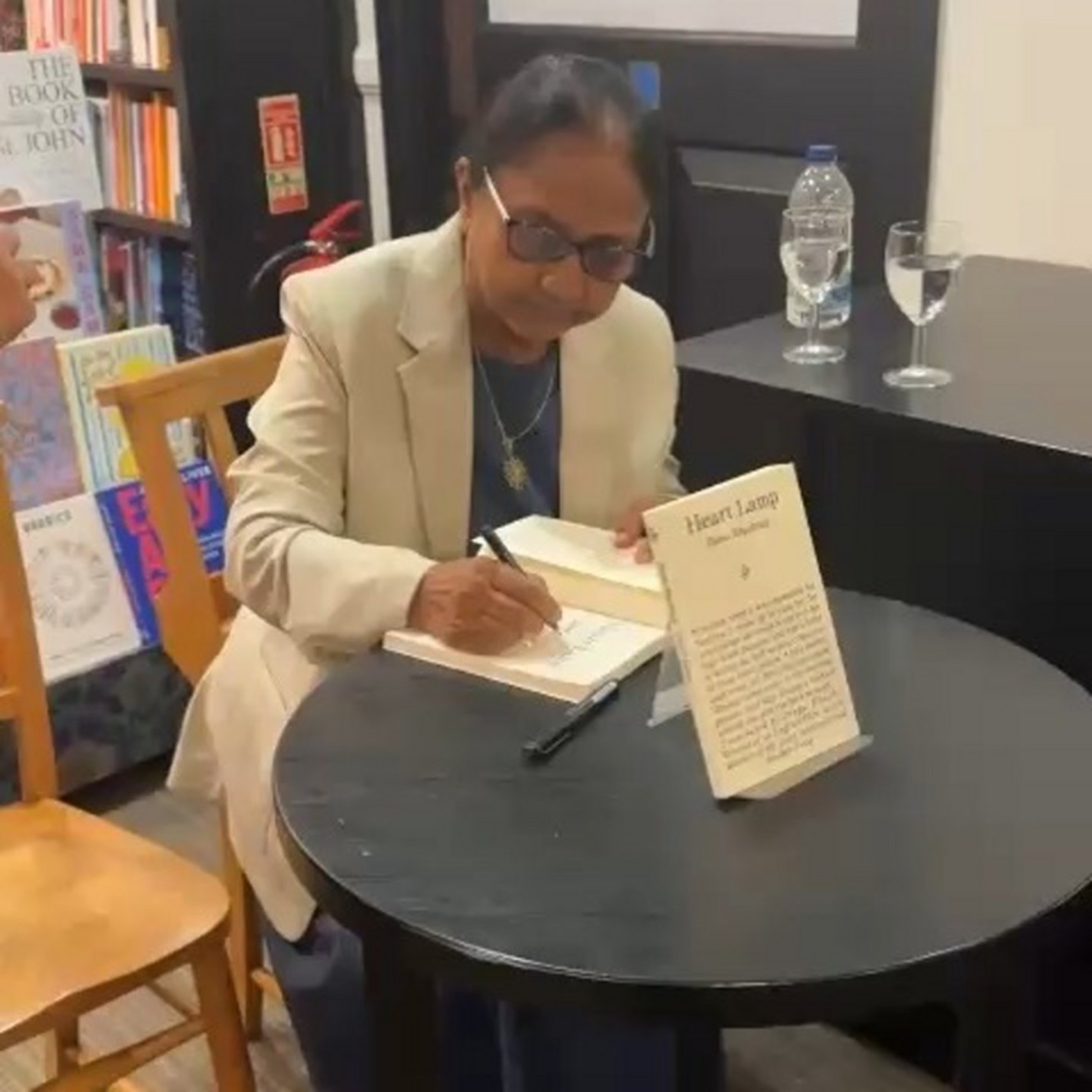

Writer, journalist, social activist and lawyer, Banu Mushtaq made history as the first ever Kannada language author to win the International Booker Prize for ‘Heart Lamp’, an anthology of short stories.

By Kakoli Nandi

Heart Lamp’ is a powerful compilation of 12 short stories written by Banu Mushtaq over a span of 33 years, from 1990 to 2023. The stories, originally penned in Kannada, have been translated into English by Deepa Bhasthi, who shares the prestigious Booker Prize, and its £50,000 prize money, with Mushtaq. Notably, ‘Heart Lamp’ is the first-ever short story collection to win the Booker.

The stories are a piercing critique of male patriarchy, with women — and often children — bearing the brunt of a system steeped in cruelty and control. Banu Mushtaq’s use of dark humour and irony cuts deep, adding texture and bite to her narratives.

Among the most heartrending pieces is ‘Black Cobras’, which portrays the brutal abandonment of a young woman and her children by her husband. The story was adapted into an award-winning film by acclaimed director Girish Kasaravalli. In ‘Red Lungi’, Mushtaq explores the disturbing lack of hygiene at a mass circumcision event, while ‘Soft Whispers’ bravely confronts the uncomfortable reality of a little girl’s encounter with sexual aggression, and the haunting residue of that memory into adulthood.

‘Stone Slabs For Shaista Mahal’ exposes the hollow romanticism of a husband, while spotlighting a young daughter forced to sacrifice her education and dreams to shoulder the burden of household chores and childcare. In stories like ‘High-Heeled Shoe’ and ‘The Arabic Teacher and Gobi Manchuri’, Mushtaq takes a sharp, satirical look at the strange and often selfish obsessions of men, obsessions that come at great emotional cost to the women around them.

Some stories are unapologetically critical, calling out the hypocrisy of preaching one thing and practicing another. Yet, in ‘A Decision Of The Heart’, Mushtaq surprises with a note of tenderness, portraying a man caught between the expectations of his domineering mother and assertive wife. Here, she offers a rare moment of empathy for a male character, acknowledging the emotional toll such familial balancing acts can take. As she received the Booker, a visibly moved Banu Mushtaq declared: “The moment feels like a thousand fireflies lighting up a single sky!”

Excerpts from the interview…

Did you expect to win the Booker?

When ‘Heart Lamp’ was long-listed for the Booker Prize, being among the shortlisted candidates was a great honour in itself. I thought it would be an opportunity to look around London. However, my readers from Karnataka had more lofty expectations. They almost commanded, “You must come back with the Booker!”

Your Booker experience came with a lot of drama and tension.

The airlines misplaced my luggage, which contained my clothes and essential medicines – I had heart surgery a couple of years back. The luggage did not arrive before the award ceremony, and with a lot of effort, I had to fetch the medicines from India. When I narrated my missing luggage ordeal on social media, none of my well-wishers back home showed any sympathy. They said, “Forget about the luggage. Make sure you win the Booker Prize.” Y

our stories are set in Karnataka’s heartland, reflecting the trials and tribulations of simple people from the Muslim community. They often challenge male patriarchy and domination. Are they inspired by your years as a social activist?

I have always spoken in favour of women’s rights and championed against all forms of oppression. My inspiration comes largely from the people and communities I’ve worked with. Everyday incidents reported in the media and my own lived experiences have deeply influenced and shaped my storytelling.

My stories centre largely on women, on how religion, society and politics demand their unquestioning obedience, often subjecting them to inhumane cruelty and reducing them to mere subordinates.

The International Booker Prize jury has lauded your writing as ‘witty, vivid, moving’ and praised your ‘life-affirming stories’, which boldly speak about women’s reproductive rights, faith, caste, power and oppression. The jury was moved by the astounding portraits of survival and resilience. Why do you think stories on the lives of Muslim people of remote Karnataka struck a chord with the International Booker Prize jury?

I feel no story is too small or too local. A tale born under a banyan tree in my village can cast a shadow as far as the International Booker Prize stage. Literature has a universal quality to reach out to diverse people across the globe. Literature teaches us to unite, embracing our diversity while celebrating our differences and uplifting one another.

You were an active part of the Bandaya Sahitya Movement, which revolutionised Kannada literature in the 1970s and ‘80s. Please tell us about those days.

In the 1980s, Karnataka was a hotbed of social movements — the Dalit movement, the Kisan movement, the feminist movement, and the environmental movement — all of which converged with the progressive Bandaya literary movement. Bandaya, which means ‘protest’, marked a powerful shift in Kannada literature by amplifying the voices of marginalised communities. It challenged entrenched social and economic injustices and became a rallying cry for equality, resistance, and reform.

You have come a long way since the time you wanted to take your own life, while battling with post-partum depression.

Though I was an educated woman growing up in a liberal family, I was forced to give up my teaching job after marriage. I had a love marriage and my husband, who was my senior in college, loved me for my outspoken qualities and active participation in debates. However, after marriage, expectations of a conventional domestic life within the confines of four walls were getting to me and I was very depressed thinking that my life was only going to be confined to the role of a wife and mother. My husband, who has always been very supportive, saved me in time.

What do you have to say about the importance of translations to help a book reach a wider audience? Deepa Bhasthi, who also shared the Booker Prize with you, has translated your stories into English beautifully, keeping the local colloquial flavour intact. Deepa has called her translation process “translating with an accent.”

It was Deepa who selected most of the stories for the anthology ‘Heart Lamp’, although I also suggested a few. Her sensitive translation into English has brought my writing before a larger international audience. I did not interfere with her translation and gave her a free hand. More books should be translated from Indian languages into English. The government should do something to encourage more translations.