Ramesh Sippy’s journey in Indian cinema spans five decades, filled with iconic films, unforgettable characters, and stories that continue to resonate across generations. As ‘Sholay: The Final Cut’ was re-released in cinemas in December 2025 with the original ending, it coincided with Sippy’s 50th anniversary in Indian cinema. Here, we get Sippy to reflect on a life lived fully…

By Andrea CostaBir

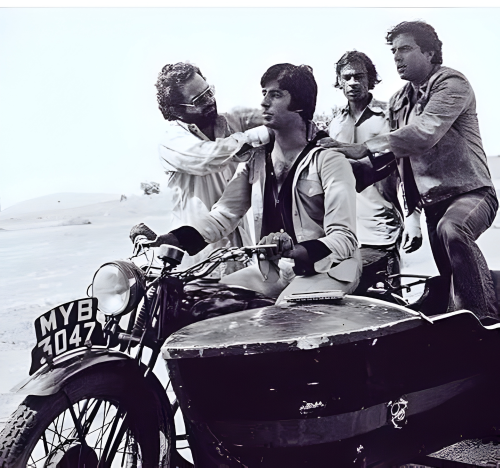

Long before ‘Sholay’ made him a legend, Ramesh Sippy learnt filmmaking the old-fashioned way. The son of producer GP Sippy, he spent his formative years on studio floors, even turning up briefly as a child actor in ‘Shahenshah’ (1953). By the 1960s, he was firmly behind the camera, assisting in production and direction on his father’s films such as ‘Mere Sanam’ (1965), ‘Raaz’ (1967), and ‘Brahmachari’ (1968), absorbing the rhythm of large-scale Hindi cinema from close quarters.

After several years of this hands-on training, he stepped out on his own by directing ‘Andaz’ (1971), a hit romantic drama; and followed it up with ‘Seeta Aur Geeta’ (1972), a runaway success that revealed his instinct for pace, humour, and audience appeal — all quietly preparing the ground for ‘Sholay’.

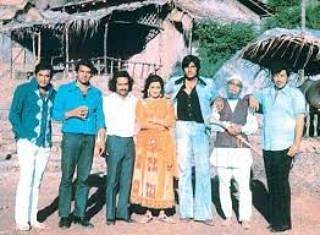

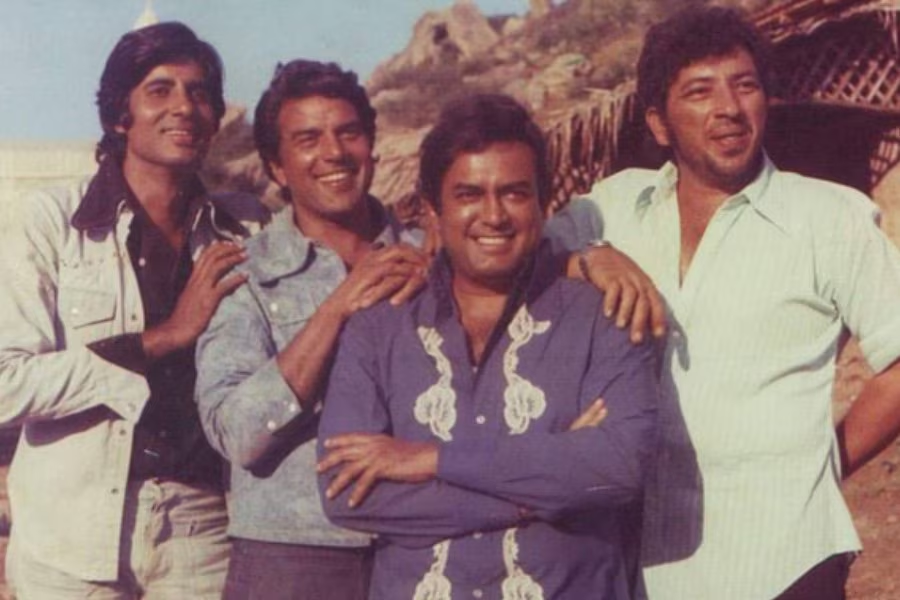

50 years after the release of ‘Sholay’, Ramesh Sippy’s magnum opus returns to cinemas in a fully restored 4K edition, complete with the original ending. For Sippy, witnessing the film’s enduring resonance is a deeply personal experience. From the camaraderie on set to the intense emotional stakes of his storytelling, and from working with actors like Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Hema Malini, Jaya Bachchan, Sanjeev Kumar, and Amjad Khan to guiding the next generation through his film academy, Sippy’s life is inseparable from the world of cinema. In this conversation, he opens up about his creative philosophy, mentorship, family and more — offering deeply personal insights…

Excerpts from the interview…

‘Sholay: The Final Cut’ was re-released in cinemas on December 12, 2025, in a fully restored 4K edition that shows your original ending for the first time, and it coincides with your 50th anniversary in Indian cinema. What emotions does it stir in you to see ‘Sholay’ celebrated in this way and reconnecting with audiences on the big screen?

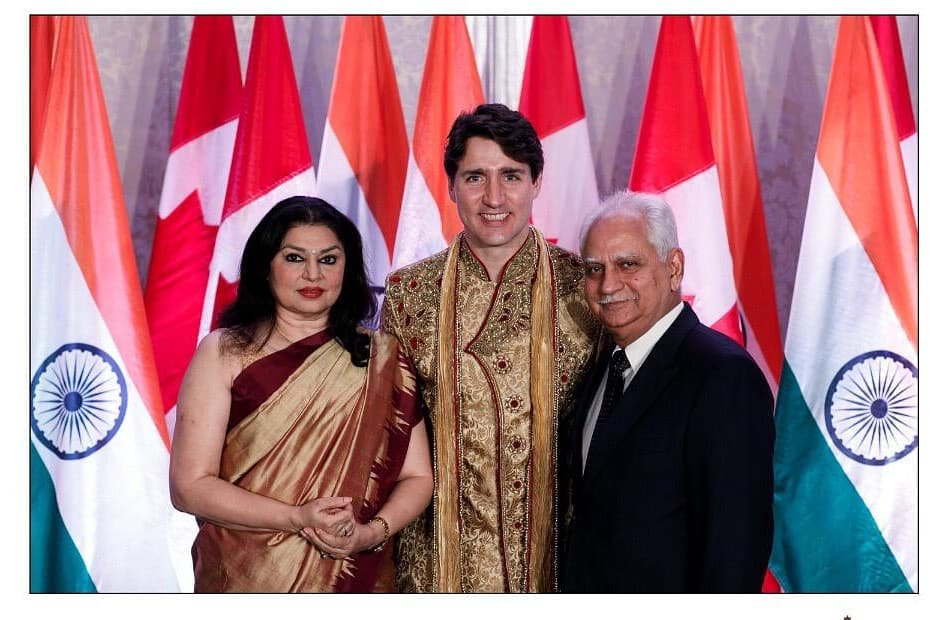

Well, it’s a great feeling, I think. First, absorbing the fact that 50 years have passed since ‘Sholay’ was released. I was in Toronto recently for the International Film Festival, and that’s when I saw it after a very long time, with packed theatres of Torontonians. I couldn’t believe I was sitting in Toronto. I thought I was back in Mumbai, when the film was released 50 years ago.

It was quite amazing. Absolutely. At the same places, the same dialogue repeating, clapping, laughing. Whether it was Asrani or Surma Bhopali, or the lovely camaraderie between the two, Veeru and Jai, and the romances. Dharmendraji and Amitji were so good that it felt like real life.

There was so much fun. When it was time for drama, the drama was there. The music was there. The background score swept everything and gave it that expanse of stereophonic sound. The hugeness of the film came through with that sound. The visuals were beautiful, but the sound added so much to it. So it was great, yes.

When you reflect on ‘Sholay’s’ journey — from its original release and initial reactions to its current status as a cultural touchstone — what do you think has allowed it to resonate so profoundly across generations?

You tell me. I don’t know. I didn’t intend for it to become what it has become. What I intended was to make a good film. I put in my best effort, and I got my team of some of the finest talents — fine actors, fine writers, fine musicians, fine lyricists — all put together, along with great background music.

They brought out a film that became memorable, and none of them expected that 50 years later the reaction would be the same. We all expected the film to do well. We had achieved something that we had worked hard for, and we were able to put forth a film that ultimately went to the audience beautifully. “It’s very sad that Dharamji is no more with us, but he will always live through Veeru, and for the audience as well. But for us, for me in particular, yes, definitely a great loss. For the industry, definitely a very big loss. For his family, obviously a very big loss.”

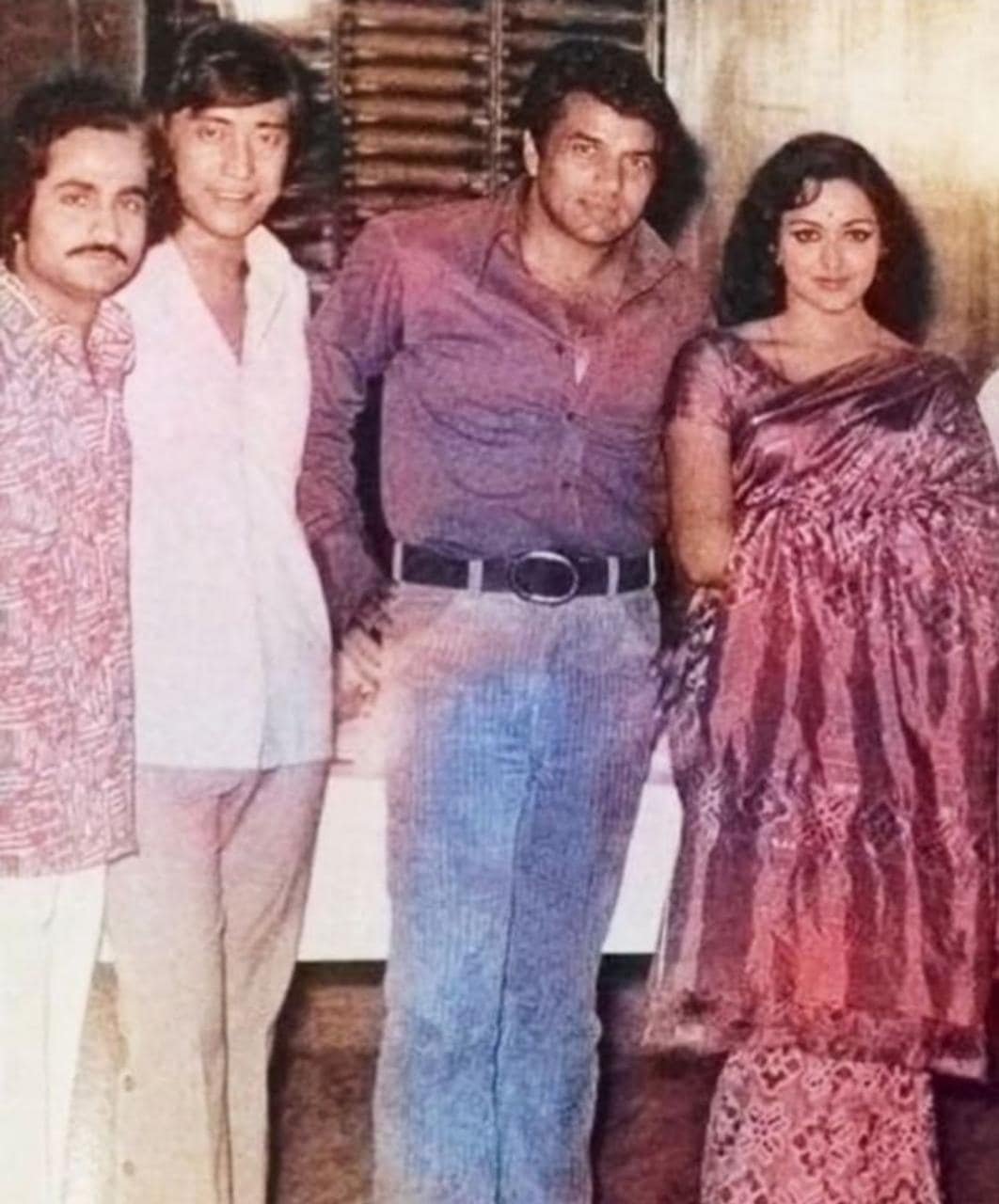

With the recent passing of Dharmendraji — a towering presence in ‘Sholay’ and a close friend — how would you describe your personal and creative bond with him over the years? What do you remember most from your time working together?

Well, it’s very sad that Dharamji is no longer with us, but he will always live through Veeru, and for the audience as well. But for us, for me in particular, yes, definitely a great loss. For the industry, definitely a very big loss. For his family, obviously a very big loss.

I don’t know, it’s just so recent. Clearly, it cannot be unemotional. When I went and saw the film in the theatres, the audience was so in tune with him. They laughed with him. They were excited. He held the screen with great warmth and had beautiful moments with all the characters — Amitji, Hemaji, Jayaji, Thakur Sanjeev Kumar, Amjad Khan, all of them.

He comes through very well — very warm. He is an extroverted character against Amitabh’s introverted character. So yes, they contrast well. They have a great rapport, and you can feel it on the screen. It comes through very, very nicely.

A great deal of it has to do with the writing, which the actors brought alive, and of course, whatever I was able to do on the sets to get them into that mood. I think it has all come together very well. You’ve worked with some of Indian cinema’s most iconic actors, including Amitabh Bachchan, Hema Malini, Sanjeev Kumar and Amjad Khan.

What did those collaborations teach you about directing, storytelling and getting the best out of performers?

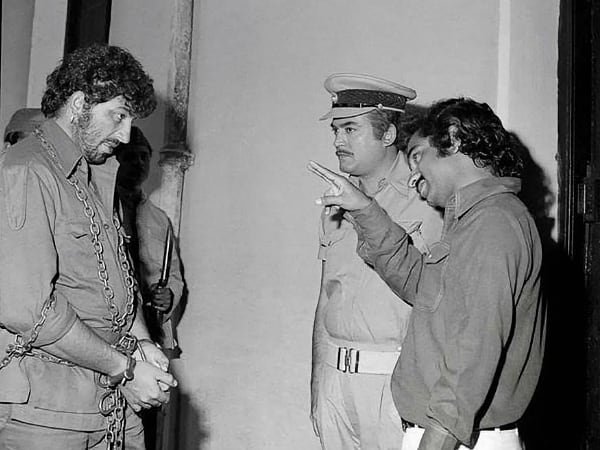

What can I say, except that to begin with, we had a fine script. Salim-Javed and I worked together. Not for a very long time — it happened very quickly — but as we were shooting, a lot of things were added and moulded. While shooting the very first sequence of Thakur coming home and seeing his family, the whole sequence changed because of the weather. It was supposed to be shot in sunlight. I shot for two days in sunlight, and then the clouds came in. I waited a couple of days, and it occurred to me — what if I shot this sequence in this weather?

The whole scene changed in my mind because of the weather and how effective it would be. How I would be able to use the wind, the uncovered bodies, as the wind picked up, along with Thakur’s emotions.

He sits on his horse and takes off. He struggles, but he is captured and tied up, and finally Gabbar has his revenge, cutting off his hands, saying, “These were the hands that put those cuffs around my hands. These are the hands I want.” And he cuts them off. It was very dramatic, very emotional, very heartbreaking.

The rest of Thakur’s journey is because of that — because of what happened to his family and because his hands were cut off. He asks for these two boys and then takes off.

I think everything played beautifully from one scene into another, and we got a powerful interval as Thakur walks away and the interval comes on his back. All in all, the combination of a wonderful script, wonderful performances, and things happening on the sets enhanced those scenes to an even greater level.

As a creative person, I found it very satisfying. I was deeply upset when the censors did not allow me to keep my original ending. It was the time of the Emergency, 1975. There wasn’t much I could argue about. They insisted that I re-shoot the scene and have the police come in and take him away. Their view was that a police officer should not be taking the law into his own hands.

I argued that this was personal vengeance, not as a police officer. His family had been massacred. What would you or I do? We had to do something emotional, something far more powerful. Just handcuffing a man and taking him to court felt inadequate. Anyway, all turned out well. Now I’m so happy that the original ending is back.

Audiences will get to see how Thakur’s final revenge was taken. Gabbar was crushed, and after that, Thakur fell to his knees and broke down. That was a beautiful moment.

Now it’s back. I’m so happy. Dharamji, as Veeru, gets down on the floor and helps Thakur gather himself. He puts a shawl around him, helps him up, and takes him away. I think it brought a very nice feeling to the end.

While ‘Sholay’ often dominates conversations about your career, your body of work includes memorable films like ‘Seeta Aur Geeta’, ‘Shaan’ and ‘Shakti’, as well as television serials like ‘Buniyaad’, among others. How do these projects reflect your evolution as a filmmaker?

I think in my life, I have not had anything fixed in mind while deciding what to make. Whatever thought comes to me, I go with it.

‘Andaz’ was very different — a widower with a little girl, and a widow with a little boy, how they come together through the children, and how it finally leads to the feeling that the children want to be together, and through them an attraction builds between the adults. They decide that it is best that all four be together.

It was a meaningful line to attempt, and very difficult. It could have been problematic, but I had fine actors again and could get the best out of them. Hema Malini playing the young widow — you feel she is too young to give up on life.

Shammi Kapoor, a fine actor, actually asked me why I wanted to do a film like this with him. He was known for dancing and lighter characters, but here he came through with a fine performance. He pulled it off emotionally. In the beginning of the film, he is himself, and then we see the other side of him. I think it all worked together very well.

And that song — ‘Hain na, bolo bolo, papa ko mummy se, mummy o papa se pyaar hai’ — summed up everything about that film.

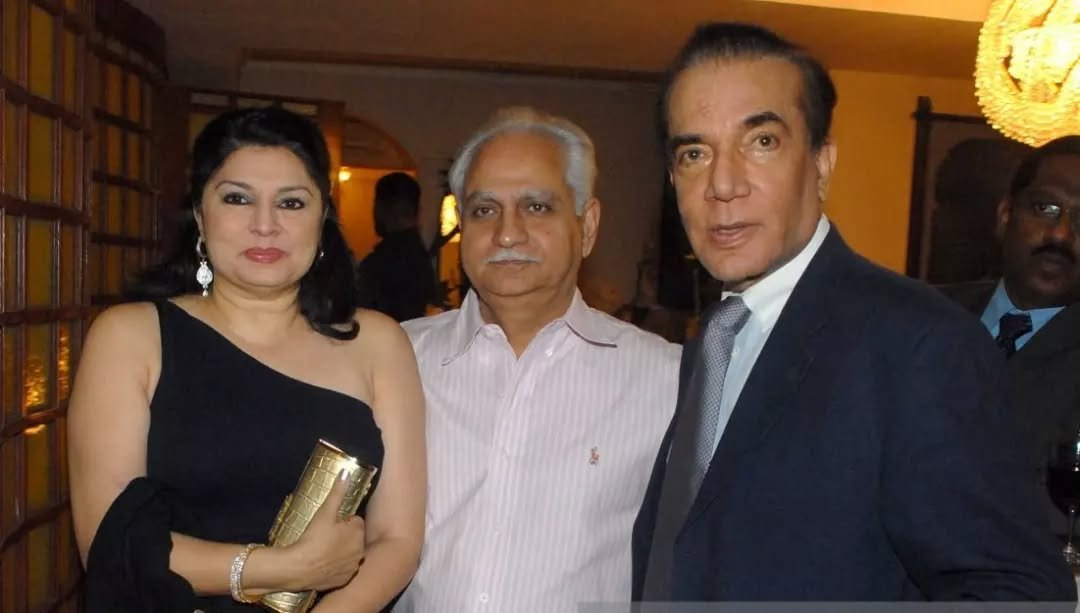

Your partnership with your wife, Kiran Joneja Sippy, spans decades both personally and creatively. Looking back, what has this relationship taught you about collaboration, balance and resilience — within both family and film?

Relationships are a continuous process over periods of time. They can improve or go wrong, but fortunately, our relationship has stood the test of time. That is on the personal side. Then there is the professional front.

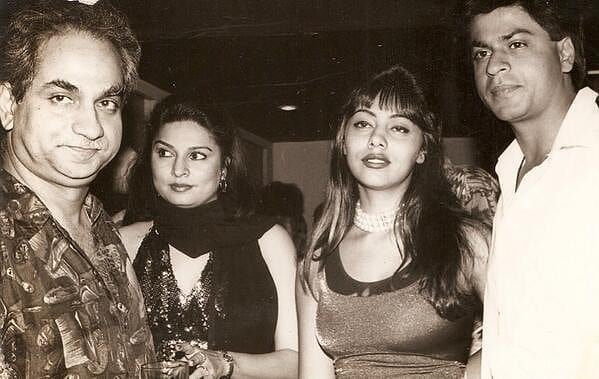

I met her during ‘Buniyaad’, in which she played the role of Veerawali. I found her to be a dedicated artiste who was interested in learning. I was able to mould her into the character because she was quick and receptive. She rose to the role very well.

We were also fortunate that Manohar Sahab Joshi, the writer, had done a marvellous job. I think he was one of the best television writers ever. She picked things up easily. With a little coaxing or minor corrections here and there, she understood the correlation between her looks, the camera, the character, and what the director wanted from her. She worked hard, and when the relationship turned personal, she started taking on other responsibilities.

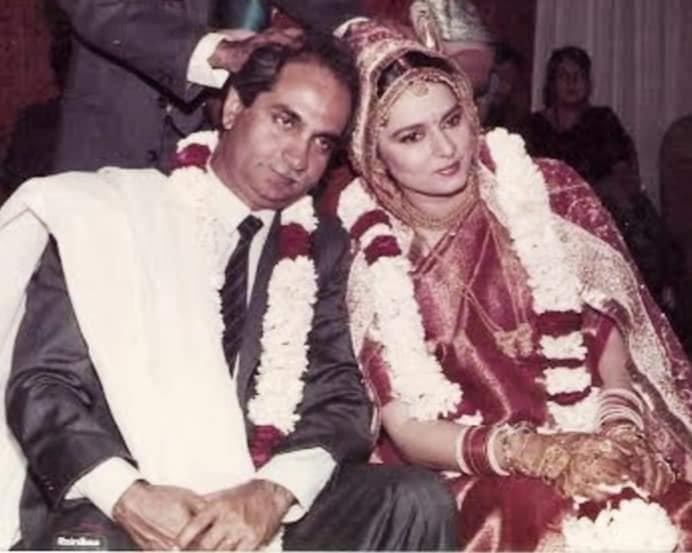

We got married in 1991. After that, she took a more active part in the serial ‘Kismat’. We did the film ‘Zamana Deewana’ together, as well as the serial ‘Gaatha’ and a comedy serial. She also did ‘The Kiran Joneja Show’ on Star.

I think we built a good rapport. She understood things well, took her career forward, and kept our relationship on an even keel. I give her credit for keeping our relationship intact today.

Professionally, she is now making films on her own through her company, Kiran Chitra Enterprises, producing smaller films and attempting bigger ones as well.

All in all, she has the qualities of a moviemaker. She did a serial called ‘Koppa’ for DD and was recently in the film ‘Shimla Mirchi’, released in 2020. Our professional work and our private lives continue.

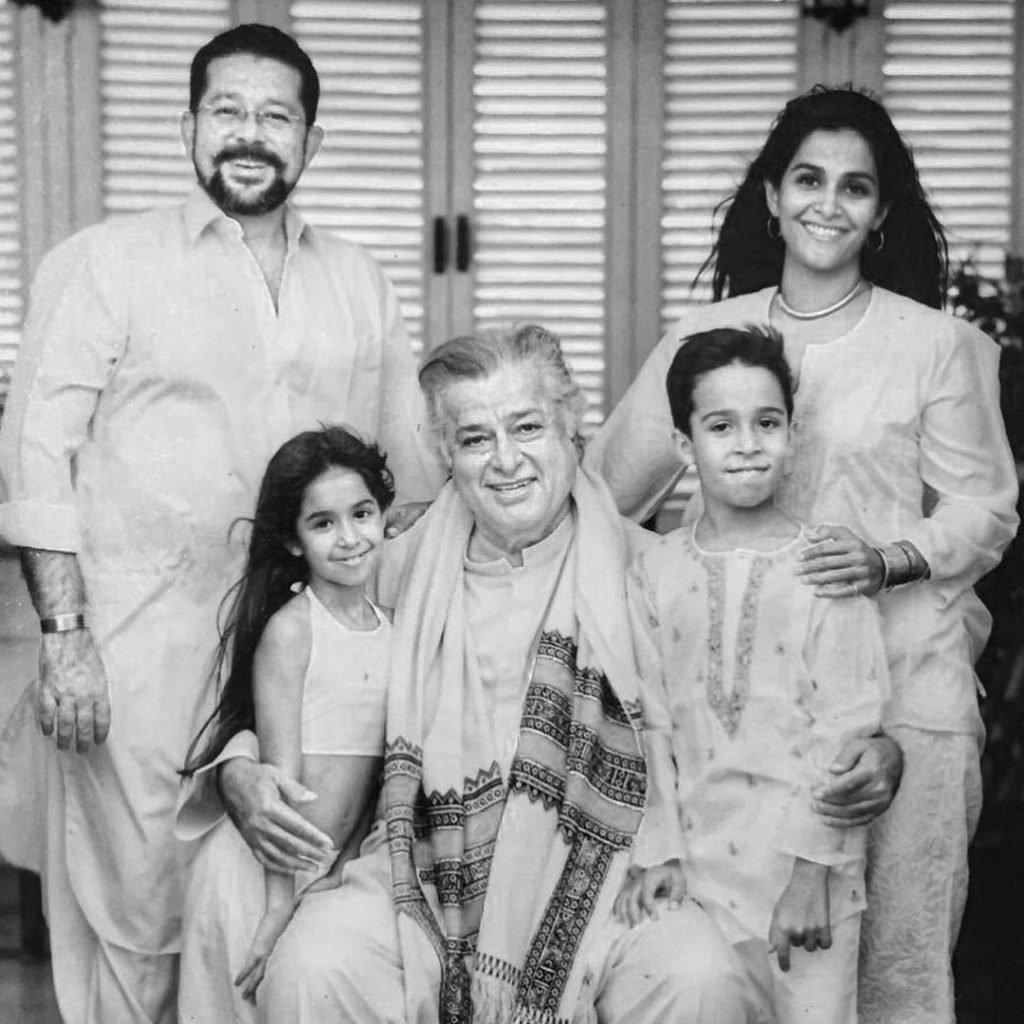

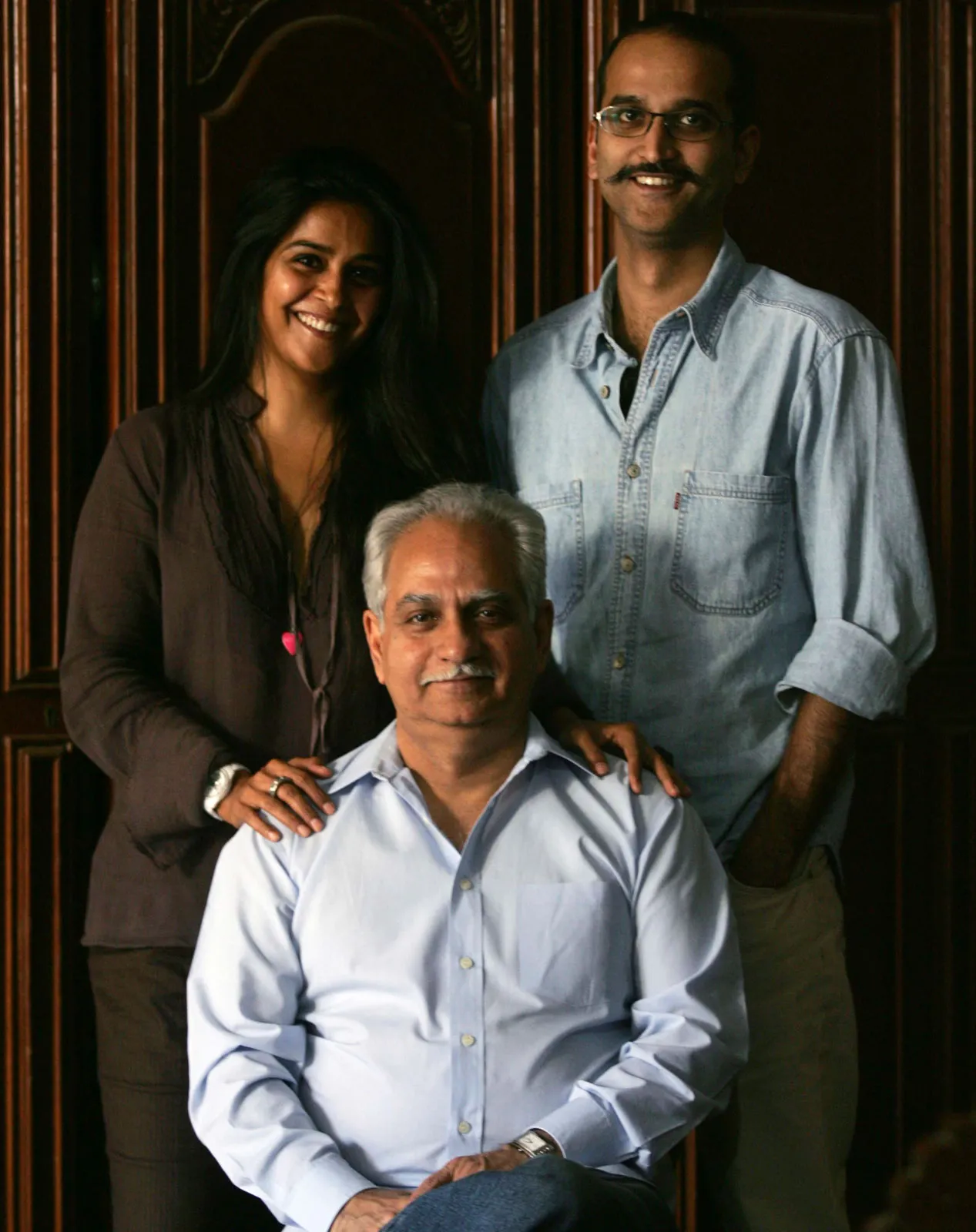

You have three children — Rohan, Sheena and Sonya — each of whom has carved their own creative path. How has your relationship with them influenced your ideas about family, creativity and mentorship over the years?

My children have joined the industry, each following their own creative path within and beyond our company. My eldest, Sheena, developed a deep fascination with photography and has truly excelled in it. She worked with me on a couple of films and did a very good job before moving on to pursue her own independent career.

My second daughter, Sonya, also inherited a creative tendency. In her younger years, she worked with Channel V. She later went abroad to study at Brown University, where she met her future husband and settled down. She has continued to lead a diverse and satisfying life, including teaching yoga classes.

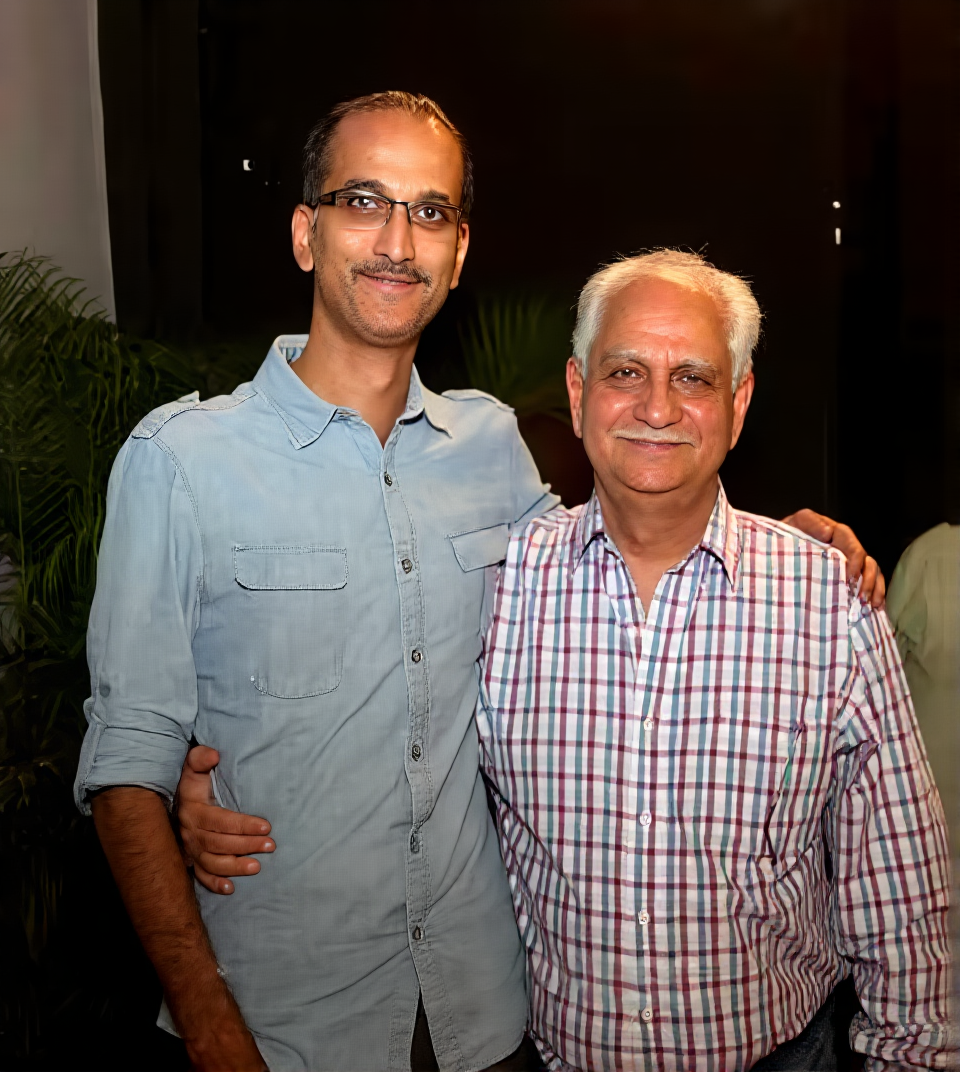

Finally, there is Rohan. His inclination was always towards filmmaking. After studying at Stanford, he returned in 1992 or 1993 and joined the family business. He apprenticed as an assistant before directing ‘Kuch Naa Kaho’, released around 2002 or 2003.

While ‘Kuch Naa Kaho’ was a mature and nice film, it wasn’t as commercially successful as we had hoped. However, he more than made up for it with ‘Bluffmaster’, a big hit starring Abhishek Bachchan and Priyanka Chopra.

His third film, ‘Dum Maaro Dum’, was set in the underworld of Goa and had a different cinematic grammar. It starred Abhishek Bachchan, Bipasha Basu and Rana Daggubati, with a special appearance by Deepika Padukone, and was co-produced with 20th Century Fox.

Rohan has continued to do well in films and television. Recently, he has been involved with the ‘Criminal Justice’ series for Applause Entertainment. I also co-produced ‘Yeh Saali Aashiqui’ with Siddharth Roy Kapur, which aired on Netflix.

All in all, I am proud that they have done well for themselves, and I wish the best of luck to my children and my wife, Kiran, as we all continue our journeys.

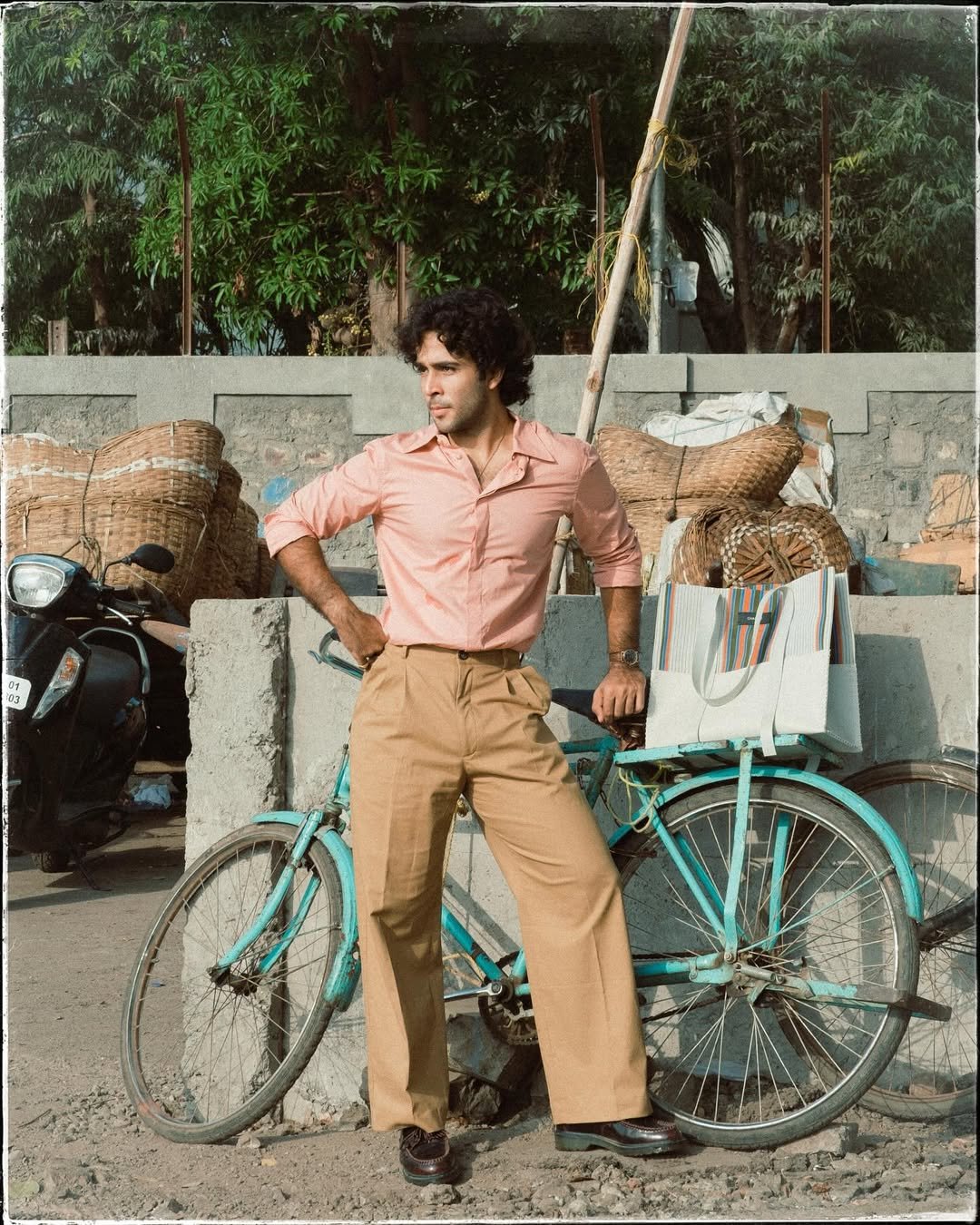

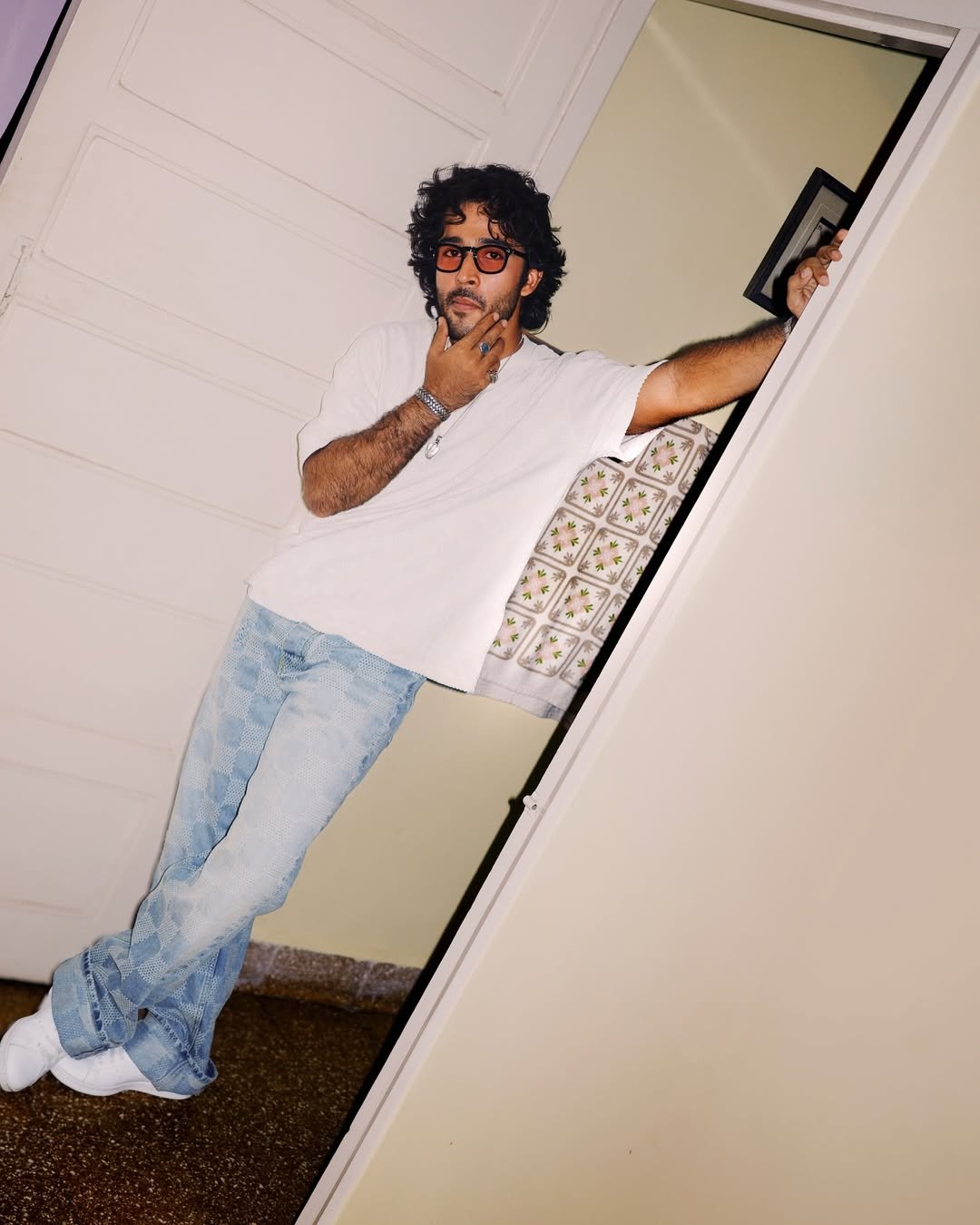

Your grandson Zahaan Kapoor has now entered films, continuing the family legacy. What has it been like watching this new generation step into the cinematic world?

Zahaan has been a very busy boy and has worked hard at Prithvi Theatre, which his paternal grandparents, Shashi Kapoor and Jennifer, established in Mumbai.

He and his sister, Shaira, have both worked at Prithvi alongside their father, Kunal Kapoor. While Shaira has worked in set departments, he has become an actor and has done some wonderful work, including his role in ‘Black Warrant’.

I believe he is showing great versatility and talent, which will continue to grow. They will always have my blessings, and I wish them all the very best.

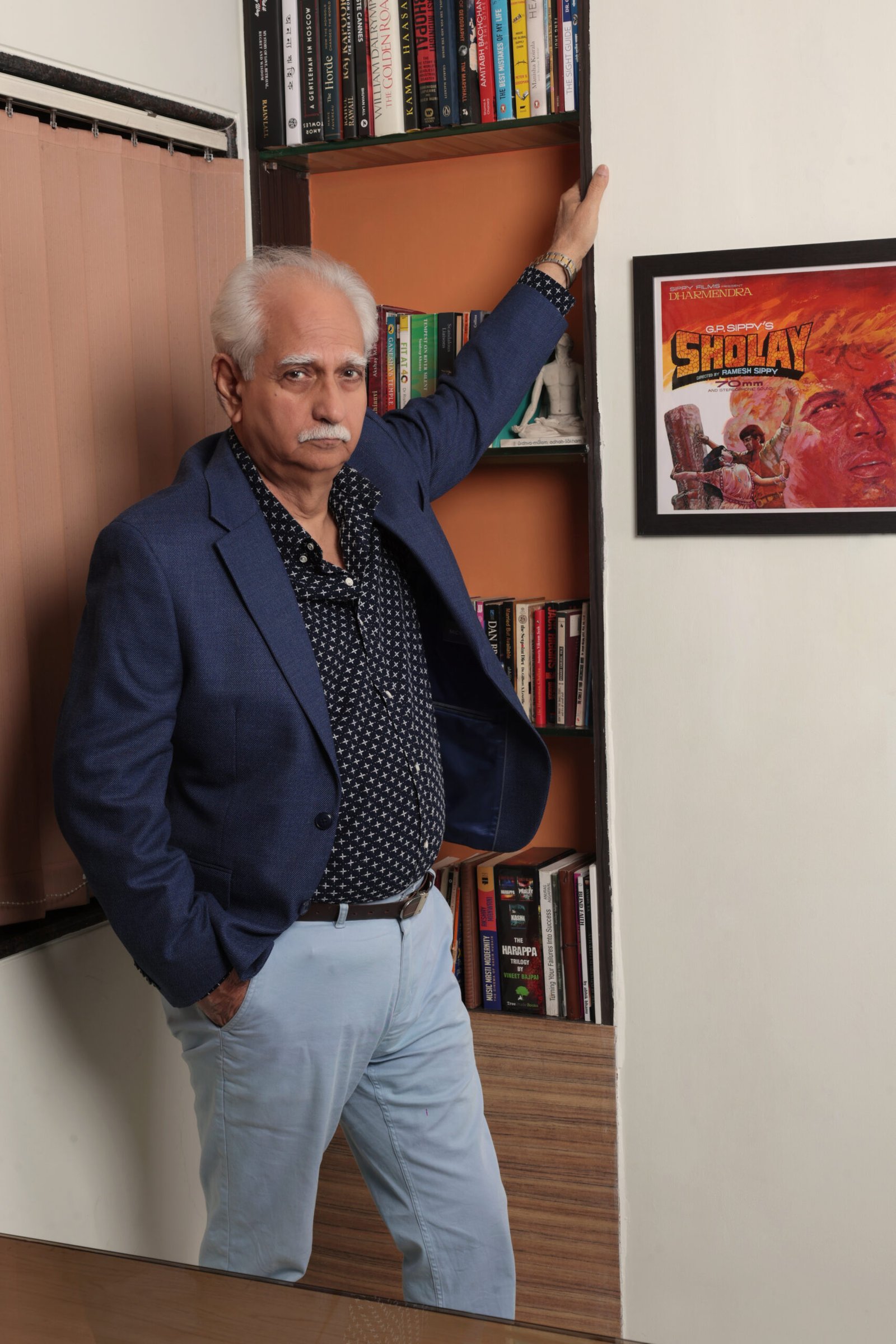

You founded the Ramesh Sippy Academy of Cinema & Entertainment (RSACE) to share your experience with aspiring filmmakers. What inspired you to start a film school, and how do you see it shaping the future of Indian cinema?

There comes a time when you feel you have made some very good films, and if it is possible to leave a legacy, then the waves should continue through young people who want to make films.

I wanted to help them in the early stages with practical education, not just bookish learning. Theory is important when writing a script, but ultimately it leads to the final film — with background music and all aspects of filmmaking understood.

At the end of the three-year term, students make their own films. Their own maturity and decisions take them forward. We have had a student, Advait, whose film has travelled to festivals around the world, including Cannes.

It is a wonderful feeling. My wife, Kiran, has been extremely helpful and runs the academy. I participate where I can, but she is the main force. So far, it has been wonderful, and I hope it continues to grow. I wish the students all the best.

Cinema has transformed dramatically with the rise of OTT platforms, global audiences and new forms of storytelling. What excites you most about these creative possibilities, and how do you see the industry evolving?

OTT is a fine innovation. Its growth happened during Covid, when people were at home watching entertainment. That is when it really took root.

Now it is a definite platform for film and web series. Seasons allow long storytelling. Films that do well in theatres also do well when they come to OTT.

Audiences have choices. Some watch longer series, others watch films. It is a healthy medium. Yes, there is competition, but it is healthy competition.

You’ve spoken before about wanting to continually “make something better than ‘Sholay’,” not as a remake but as a creative challenge. How do you keep that curiosity alive, and what kinds of stories energise you today?

First of all, I never tried to make ‘Sholay’ when I made ‘Sholay’. I tried to make a damn good film.

Every time I decide on a subject, I aim high. ‘Andaz’, ‘Seeta Aur Geeta’, ‘Shaan’, ‘Shakti’, ‘Saagar’, ‘Buniyaad’ — all different genres. Each is a saga in its own way. If I do more work, it will be with the same zest and energy I have always had.

Looking at your remarkable journey — from classic filmmaking to mentorship and legacy building — what would you like audiences and future storytellers to remember most about your contribution to Indian cinema?

I would be happy if they remember that each of my films was different and yet satisfying. I don’t make films that are difficult to understand.

They are simple, thoughtful, dramatic and entertaining. There may be disagreements, but if audiences carry the film in their hearts and talk about it, that gives me satisfaction.

Finally, beyond your films and accomplishments, how would you describe yourself at your core — the passions, values and personal convictions that have shaped who you are as a human being and an artiste?

Here, I would like to say that my wife, Kiran; my first wife, Geeta; and my children — Sheena, Sonya and Rohan — have all lived with my work taking me away from them.

Somewhere, I have not been as good a husband or father as I should have been. They have been very understanding, and because of that atmosphere, I was free to do my work with passion.

I have to thank them and apologise to them for my absences. Without them, I could not have done this. With their support, I was able to do my work with all my heart. I hope I can make it up to them in some way, even though it will never be the same.