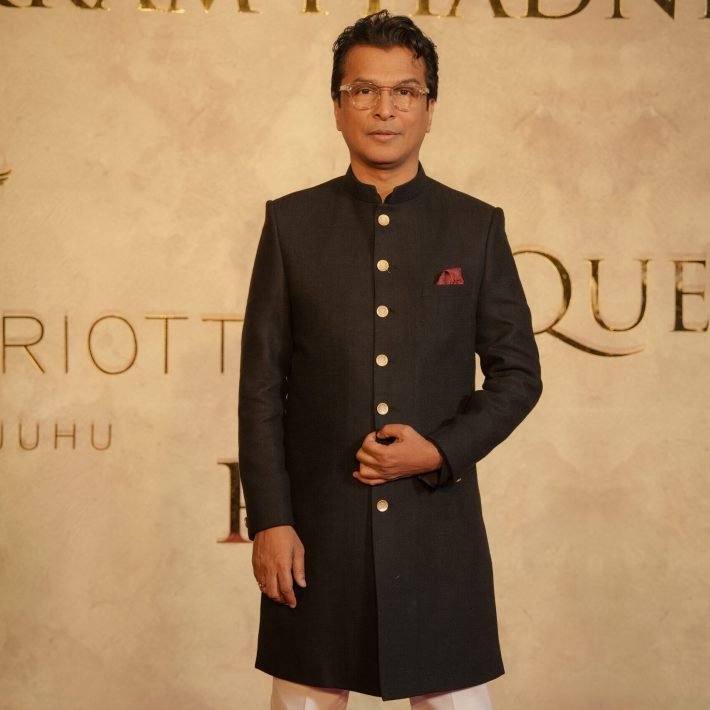

From moment marketing to theatre and films, Rahul daCunha’s creativity has not only kept pace with the times — but often set the tone, staying one step ahead in both relevance and resonance.

By Nichola Marie

Sharp, self-aware and refreshingly unfiltered, Rahul daCunha walks us through the many creative avatars he’s worn over the years — and why storytelling, in any medium, must always come first.

Excerpts from the interview…

The Amul ads are nothing short of iconic. What, in your view, has kept them relevant for nearly six decades?

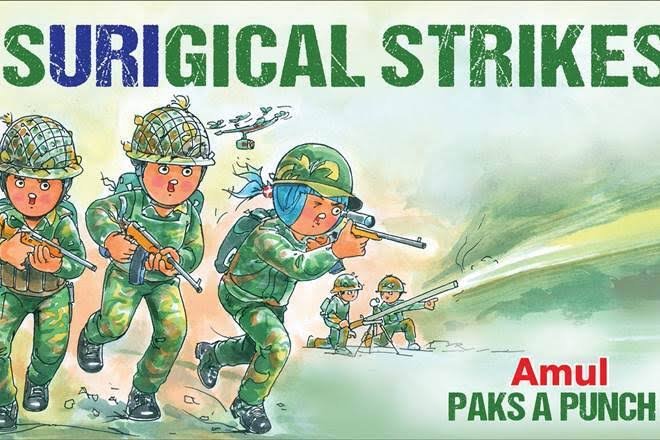

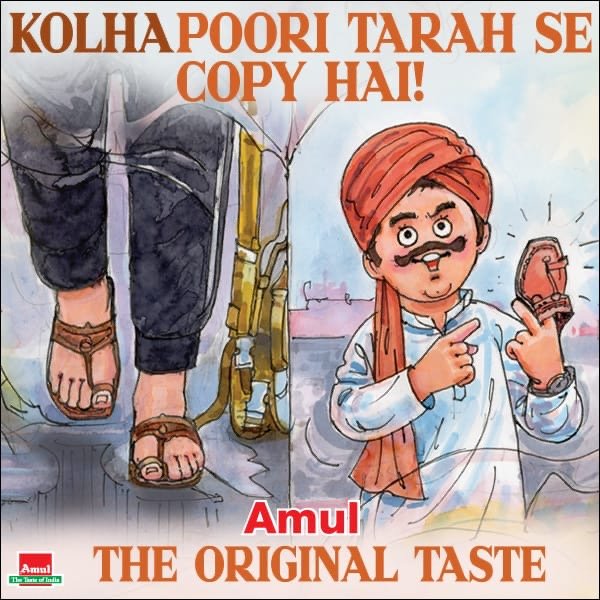

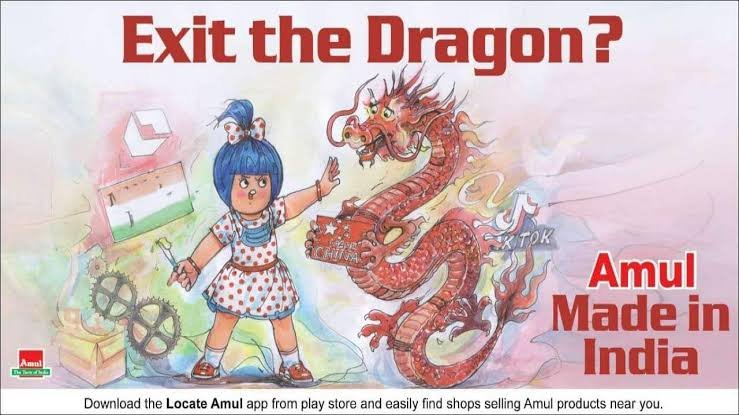

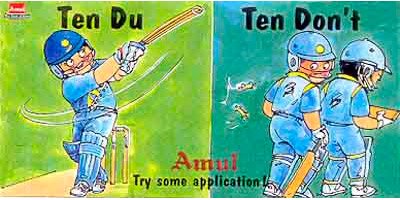

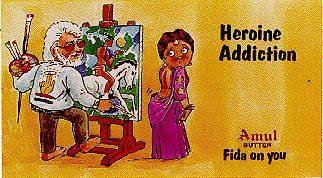

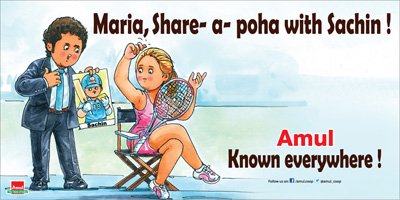

My father (Sylvester daCunha) started them in 1965 — so yes, we’re at the 60-year mark now. Back then, ads would appear maybe once a month. Hoardings were all we had — no TV, no newspapers because they were too expensive and too transient for topicality. Today, with social media, we do about one every day and a half — 170 to 180 a year. What’s fascinating is, we were doing moment marketing before it became a term. We were doing memes before memes had a name. The Amul Girl has always responded to what’s happening around us — cricket wins, elections, movie releases, even odd things like the Prada-Kolhapuri chappal series. So when everyone today is reacting online, we’re just doing what we’ve always done — but faster.

And yet, Amul ads still manage to strike the right tone — clever, cheeky, but never crude. How do you manage that balance in such a polarised digital age?

That’s a very conscious line we never cross. The Amul girl is cute — so even when there’s a dig, it comes with a smile. There’s humour, even satire, but never malice. We’re not trolls. There’s a difference between being edgy and being nasty.

Also, we always remember this is a brand. It’s not someone venting on Twitter. It has to be responsible, it has to reflect values. That kind of restraint, I think, gives the campaign longevity. We don’t punch down.

The client-agency relationship between Amul and your agency is one of the longest-running in the country. How has it stayed strong for 60 years?

Trust. That’s the foundation. From Dr Kurien, who gave my dad the original license to create the campaign, to Jayen Mehta, the current MD — they’ve always let us steer the creative. But, in turn, we’ve always been careful not to misuse that freedom. We know where the line is. Good relationships between clients and agencies are based on mutual understanding. The moment there’s second-guessing or control, the creativity suffers. We’ve always felt a sense of shared ownership of the campaign.

You’ve worn many creative hats — adman, playwright, director, now filmmaker. What drives you across these different mediums?

At the centre of all of it is creativity. It’s what gets me out of bed in the morning. I write every single day. That’s not an exaggeration. Whether it’s a column, a script, an idea, a few pages of dialogue — I have to write. It’s my muscle. And like any muscle, if you don’t use it, it gets lazy.

Sometimes it’s structured, sometimes not. I try and write from 7.30 a.m to 9.30 a.m every day. That’s my precious window. No distractions, no calls. After that, the world kicks in — emails, meetings, floods, white ants, traffic. But that quiet time to write is sacrosanct.

You mentioned your father. What are some things you inherited from him — personally and professionally?

Apart from the Amul campaign, which is of course a huge legacy, I think I inherited his creative discipline. He loved ideas, words, wit. I was lucky to grow up in a family where creativity was celebrated. Not just my dad, but my mother (Nisha daCunha), my uncles Gerson daCunha and Kersy Katrak — they were all deeply creative. It was never about the money. It was about doing great work.

We weren’t conditioned to think about box office results or commercial pressures. That’s incredibly freeing. It lets you take risks, create without fear. That’s a rare privilege.

You’ve worked with some of the legends of Indian theatre and advertising. Who left a lasting impression on you?

The first name that comes to mind is my uncle, Kersy Katrak. He started MCM, one of the most legendary agencies of its time. All the giants came out of there — Arun Nanda, Mohammed Khan, Ravi Gupta. He was my mentor. He taught me to keep rewriting a sentence till it shines, that the first draft is never good enough. That you have to craft write. He was also in theatre, so he bridged both worlds beautifully.

Another important collaborator is Bugs Bhargava. We share the same passion across mediums — film, theatre, advertising. He’s a filmmaker, actor, writer. Our ideas bounce well. We understand each other’s rhythm. That kind of creative partnership is gold.

Theatre has always been central to your creative journey. What keeps drawing you back to it?

Theatre is where it all began. And it’s where I keep returning. Because it’s pure. You have no budget, no fancy locations, no CGI. All you have is performance and dialogue. You have to get the audience to imagine. I still find that thrilling. ‘Class of ‘84’, for instance, ran for over 10 years. I wrote it as a tribute to my own college years, but people saw themselves in it. That’s the magic of theatre. Everyone finds their own story.

How does theatre writing differ from film or ad writing?

In theatre, the script is the star. There are no distractions. So your dialogue has to sing. With film, I’ve begun to think more visually. Earlier, I thought of words first. Now, even for plays, I think: What does this look like? ‘Pune Highway’ was a revelation. I realised that the heart of any good film is the script. Everything else — stars, songs, sets — comes later. You need a watertight script, or it won’t hold.

Speaking of ‘Pune Highway’, what’s your big takeaway from that cinematic debut?

…That filmmaking is hard. And beautiful. OTT has changed everything. Audiences today demand more. If you’re asking them to come to a theatre, you better give them a damn good reason. It’s no longer enough to have a big star. You need a story that moves them.

And with OTT, attention spans are brutal. The remote is ruthless. If you don’t hook them, they’re off to the next show. So the challenge is: How do you create something that works on a phone screen, but has the weight of a theatre release?

What kind of filmmaker do you see yourself becoming?

Someone who tells good stories. I’m not chasing big stars or ₹100 crore budgets. I want people to say, “That Rahul and Bugs film was solid. Great story. Great performances.” I don’t want to be tied down by commercial expectations.

I want to keep my writing sharp, my casting honest. There are no small roles, only small writing. OTT allows for that. The playing field is flatter. It’s the golden age of storytelling – if you use it right.

Are you working on anything new?

Yes, I’m working on a play called ‘Pinto Apartments’. It’s a comedy about redevelopment — very topical in Mumbai right now. The plan is to stage it next year, and then adapt it into a film by 2027. That way, we test the material, fine-tune it. It’s exciting.

Are there filmmakers you particularly admire?

David Fincher. He made ‘Seven’, produced ‘House of Cards’. His screenplays are razor-sharp. I’m drawn to thrillers, to mysteries, to modern crime stories. I love the whodunit genre — the kind of narrative that makes an audience say, “I didn’t see that coming.” I want to hold an audience in suspense, give them their money’s worth. That’s what theatre taught me: Tension must never flag. Every second should matter.

What does the future hold? Where do you see yourself heading next?

Honestly, I don’t know. But I’m excited to figure it out. How do you create content for Gen Z? For millennials? For people raised on reels and AI-generated art? I’m curious about AI. Is it helping or dumbing us down? Are we simplifying too much and losing the magic of originality? I want to keep telling good stories, but I also want to understand this new creative ecosystem. Whatever comes next — theatre, film, digital — I just want to stay true to my craft.