Madhur Bhandarkar doesn’t sugar-coat, nor does he preach. Through his work, he aims to hold up a mirror to society. And if you’re offended, that’s your problem!

By Tsunami Costabir

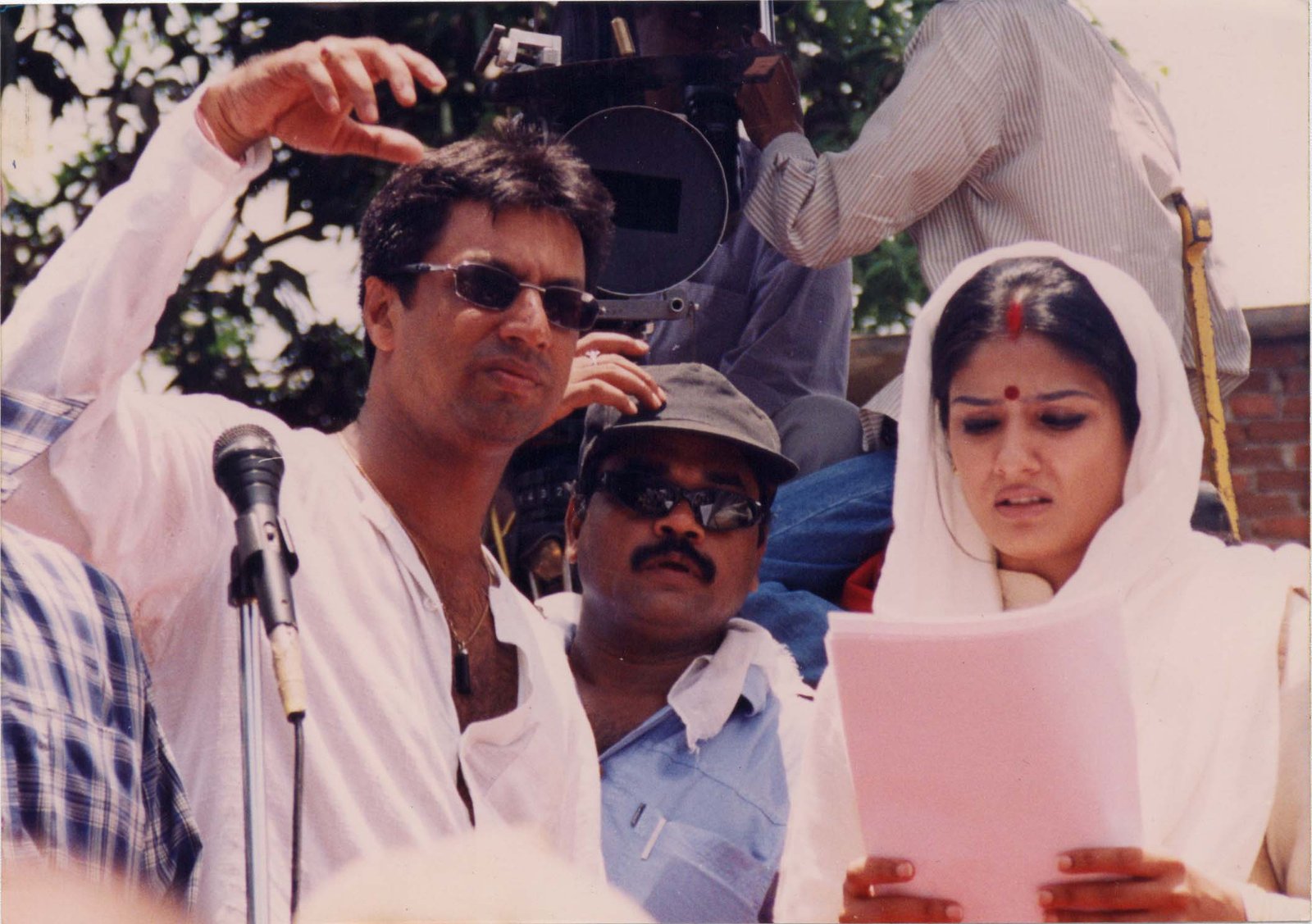

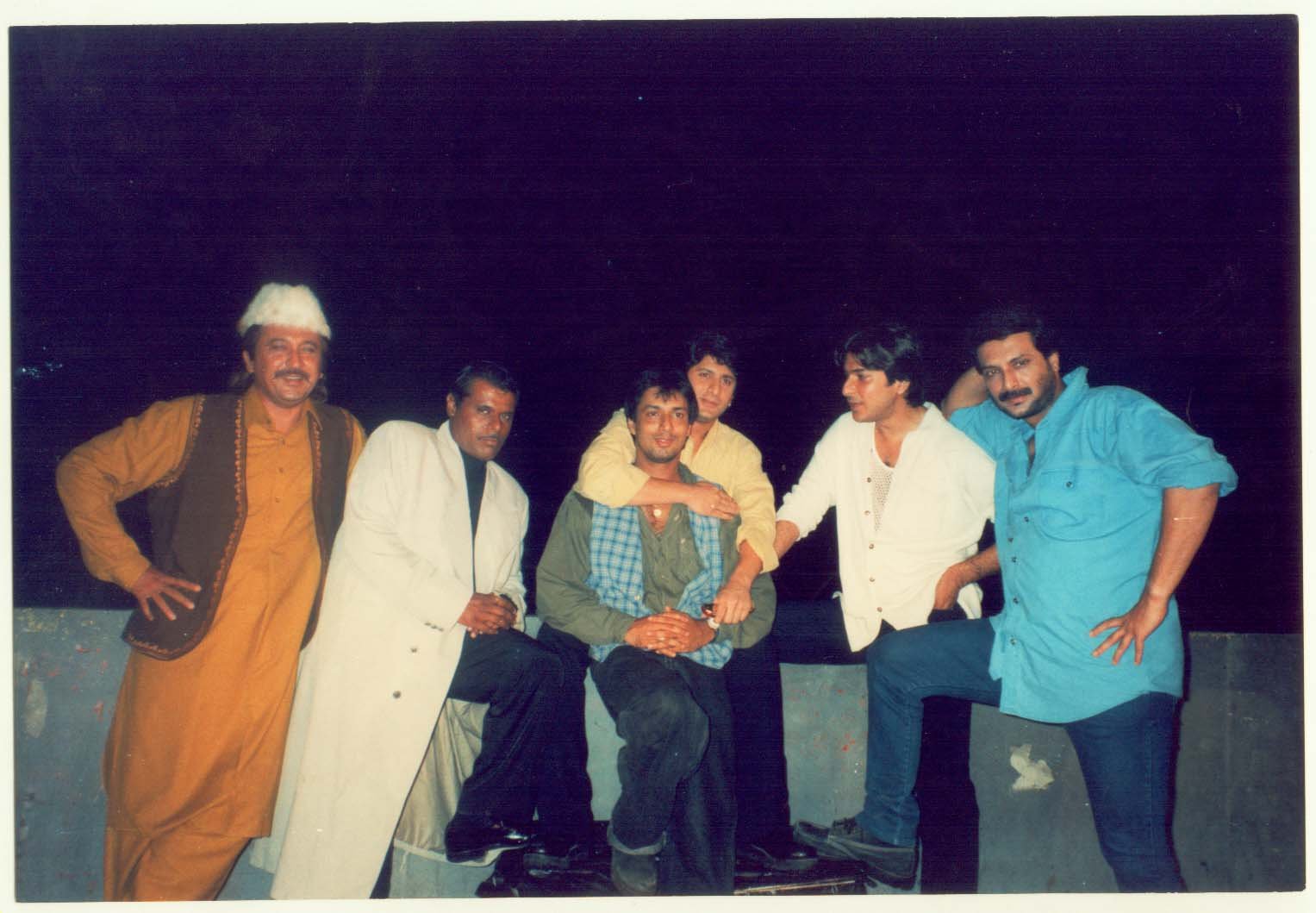

If there’s one takeaway from speaking with Madhur Bhandarkar, it’s that you need to believe in yourself before the world does. Madhur moves with conviction and has an unending zest for life. From being a video cassette delivery boy to becoming one of the most critically acclaimed filmmakers in India, his journey will inspire every cell in your being to live its full potential.

Excerpts from the interview…

You are known for making films that delve into realistic and gritty subjects. What draws you to such stories?

I think in our society and in the country, there are lots of issues – lots of topics for filmmakers and storytellers to explore. With my films, I am inspired by real-life incidents and what happens in society. It is also necessary to get the right subject and make it commercially entertaining.

I read a lot and communicate with people from different countries and walks of life. And that is the reason I can tell stories from a bar girl to the corporate world, the traffic signal, and people in fashion or films.

My filmmaking process essentially turns me into a journalist. Some people write blogs, make documentaries, or write articles; I make films.

As far as the portrayal of your films goes, how do you ensure authenticity, given a lot of them have a very sensitive nature? And how do you balance that authenticity with creating something that will draw audiences?

I do a lot of research, and I try to keep it 70 to 80% authentic with a room of about 20% for cinematic experience and artistic liberty.

Sometimes I do have a problem with people getting upset. Some of the people who my films are inspired by are my friends. And they think I’m being mean or trying to show them in a bad light. Sometimes I portray more personal issues of my life, and that, too, can create problems.

My film ‘Indu Sarkar’ made political parties upset. They protested against the film, thinking I was trying to show them as the bad ones in the political spectrum.

But, you know, I am a filmmaker and a story storyteller. And as a filmmaker, I am answerable to my audience. When it comes down to credibility, I show things from my perspective. Not everyone may agree with the way I depict situations, but I make the film the way I want to.

Do you think that your films, apart from telling a story, are trying to communicate a stronger, deeper message?

I am aware that film inspires people and leaves an impact on them even after they leave the theatre. And since I make films on real subjects, there is an audience that will believe the things I show in the film.

So when I made ‘Fashion’, after watching the film, nobody wanted to come into the glamour world. But my intention is just to show the various things happening in the world and garner curiosity. My views are not judgmental. My films are not preachy. I don’t say, ‘This is right, and this is wrong’. And a lot of my work is ambiguous. I’m not here to preach – I’m here to show a mirror to society.

What is the best compliment you’ve gotten as a filmmaker?

Today, thanks to OTT platforms, quite a lot of my content is present to be viewed. I go to a gym sometimes, where I meet young people of 20-22 years. When I made, say, ‘Fashion’, they would have been nine or ten years old. They were not aware of the movie, but they’ve watched it today.

Especially in the pandemic, a lot of people have watched my films, and they go ahead and tweet about it or DM me. There are a lot of people watching and connecting today, and that is so beautiful. It also goes to show that my work is relevant. I get told by people that I am one of the first people who has made films of this realistic nature, way before the OTT platforms started to. And I think that is the best compliment I could get.

What made you realise the power that cinema has to influence people? What made you choose it as your career?

I only ever wanted to be a filmmaker. I was a very mediocre student, but I would read newspapers and books. Reading has always been a big part of my life.

I dropped out of school, and at the young age of 12/13, I became a video cassette delivery boy. I went home-to-home on a cycle for three to four years until I got a scooter of my own. In those days, I used to deliver cassettes to people from all walks of life – from small shanties to corporates and people from the film industry. That exposure showed me that everyone watches films. I would see very contrasting worlds. That’s why my filmography can go from ‘Chandni Bar’ to ‘Corporate’ and ‘Traffic Signal’ to ‘Fashion’. I can show you issues from ‘Babli Bouncer’ to the intricacies of what happened during the pandemic with ‘India Lockdown’ – how sex workers survived, a migrant worker who walked to his village, or a lonely man surviving in the house.

Who are some filmmakers or artistes who have inspired you to tell stories the way that you do?

I am very inspired by Guru Datt, Vijay Anand, Manmohan Desai and Mani Ratnam.

Can you walk us through your filmmaking and research process – from coming up with an idea to developing the story?

Take any film – say ‘Chandni Bar’ – I went to some 16/17 bars and interacted with the waiters, the bartenders, the cooks, the rickshaw and taxi drivers outside, and the dancers. That’s how you get stories. The same for ‘Indu Sarkar’, ‘Traffic Signal’, or any of my other films. I walked every Tuesday from my house in Khar to Siddhivinayak Mandir, and I would see people at the traffic signal, selling chewing gum or books, someone begging, so I was curious about where these people come from and how they do it. That’s where the research starts.

Do you feel like people are receptive to you asking them questions, or do they get worried? Maybe some of them recognise you and know your work, making them more sceptical?

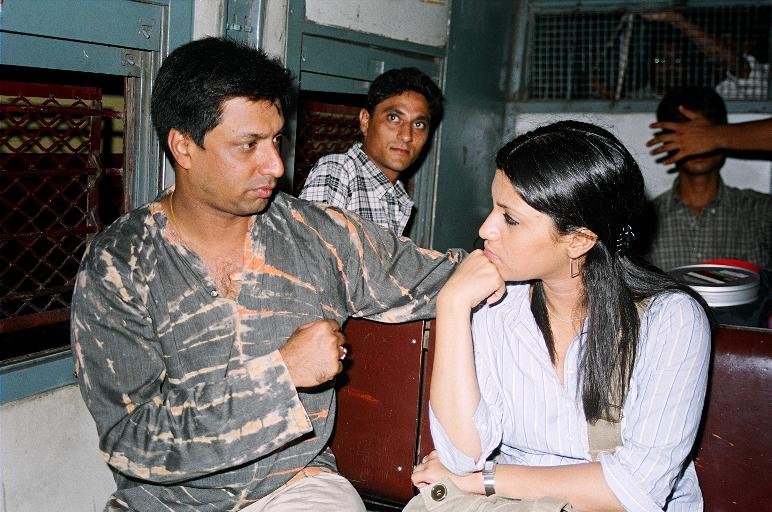

After ‘Page 3’, people in the corporate world didn’t want to give me access to them because they felt like I exposed a lot of them. But there are lots of forthcoming and supportive people too. They know that I value their privacy. For ‘India Lockdown’, Shweta Basu and I went into Kamathipura, met with the sex workers, went into their homes and kitchens, and asked them how they survived the pandemic.

I don’t want to depict something that I haven’t seen. It has to be authentic. I pay close attention to the way people speak, their language, the colloquial terms, their body language – it’s the small elements that make the biggest difference. So it’s very important for me to do background checks, interviews, and research.

In terms of the film industry at large, do you believe that films have a duty towards society beyond entertainment?

It’s all about the individual. Certain people make films only for entertainment. As for me, my films have both – they tell real stories and also entertain. I have been very commercially successful – at the box office and also in critical acclaim.

Films and cricket are great connectors with audiences in India. They are the equivalent of festivals, and they also have a large influence. I know films have even impacted my fashion sense. So it really depends on the individual. I can’t speak for the whole industry.

Cinema has no boundaries or religion. Today, on OTT platforms, we watch films in different languages from around the world, and we watch them with subtitles. Humans across the world are connected by the same lived experiences. We can all understand the trauma and happiness the person on the screen is going through. I think that is the beauty of it.

Are there any new stories or narratives you wish to explore?

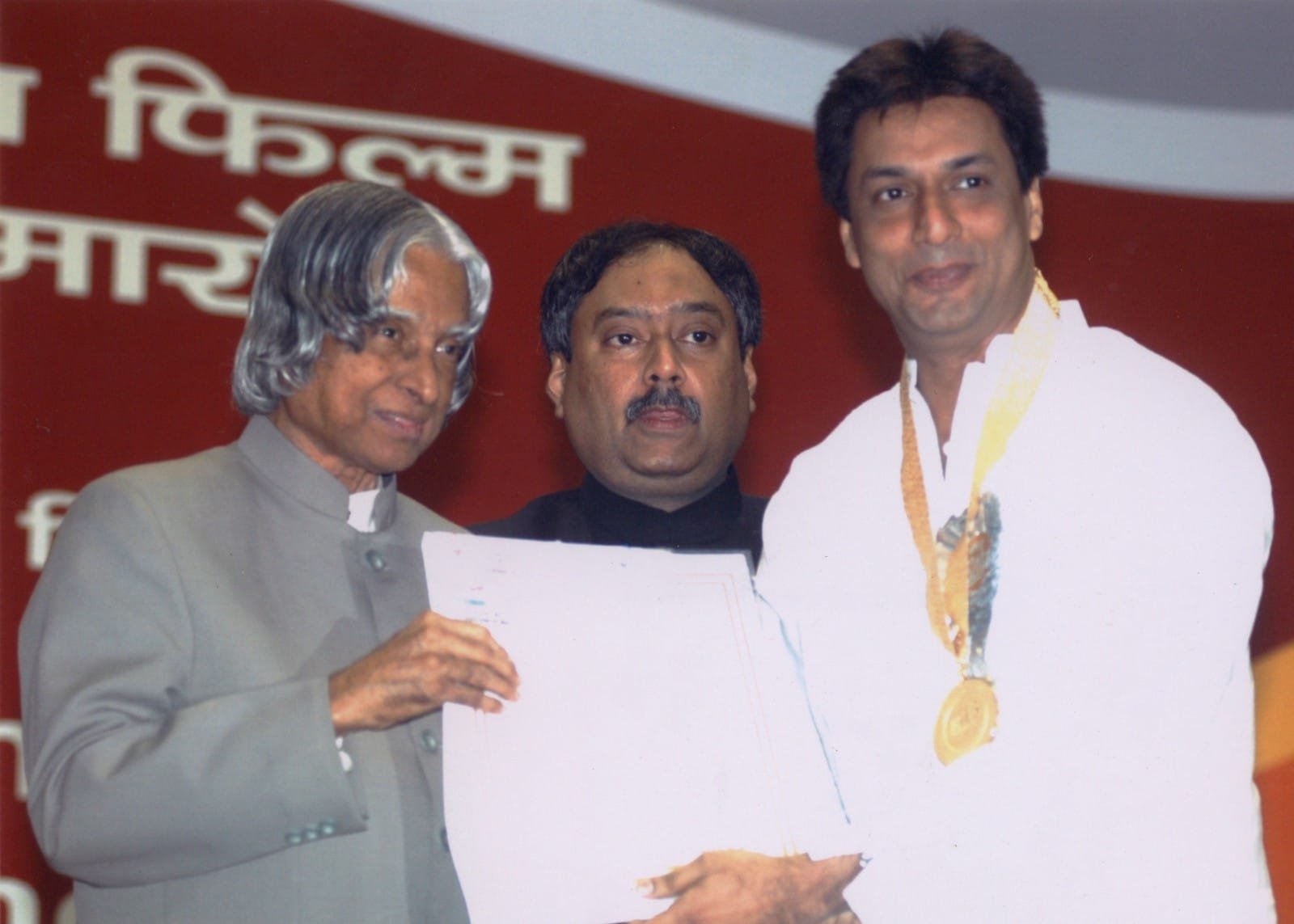

What I can tell you is that last year was great for me, with both ‘Babli Bouncer’ and ‘India Lockdown’. I also received my first National Award with my Bengali film ‘Avijatrik’. Working with OTT has also been brilliant – it is low budget but with a massive reach. Now, I’m taking some time out, travelling, and working on something really good and hard-hitting that will be released soon.

Lastly, what advice would you give aspiring filmmakers who are interested in creating socially relevant and thought-provoking cinema like yours?

I think they have to stick to their convictions – believing in themselves and what they want to make. It is very necessary to make a film you want to make. What works at the box office – nobody can tell. The actors, filmmakers and directors of the film need to believe in each other. Sometimes a small-budget film does superbly well, and a big-budget film doesn’t. What people like, we never know. So stick to your convictions and tell the stories you want to.